The history of garbage

What have we done with what we don’t need anymore? The garbag in Bergen has been a resource and a nuisance.

Ukjent fotograf / Universitetsbiblioteket UIB

Ukjent fotograf / Universitetsbiblioteket UIB Mona Maria Løberg

Mona Maria LøbergI vitit BIR’s new building at Nygårdstnagen, a building where the office section has received the certification BREEAM-NOR Excellent. “Vestlendingenes egen miljøbedrift. Alt har verdi” (“The Westerners own environmental company. Everything has value”) it says in large letters in the front. BIR is the company that takes in and processes the trash from 383 000 residents in our region. They run an incineration plant, collaborate with Eviny on district heating, and are in the process of establishing a biogas facility at Voss. Amongst other things.

Inside I meet Toralf Igesund, senior advisor in the department of development in BIR. He has worked in BIR since 1992, so he knows the story well. He begins by explaining that way back in the day trash was given to pigs and dogs.

Mona Maria Løberg

Mona Maria Løberg– There was no waste collection, because not that much was seen as waste, he says.

Society eventually changes, and the need to collect garbage becomes clear. But not everything was well with the city’s waste disposal services, Egil Ertresvaang explains in Bergen by historie part III. The municipality had left overnight renovation to a private company, who removed the waste from outdoor toilets all over the city. It was shipped to barges by Dreggen, Torvet, Muren and Nyallmenning. Three times a week it was dragged out into the fjord and dumped in the sea. Other waste was brought to Nøstet and again thrown in the sea.

Sewers became more common in the 1850’s, which fed directly into Vågen or Lilli Lungegård where it polluted the harbour basin. Daytime renovation was performed by hired help, “usually prisoners from Bergenhus fortress or detainees from the penitentiary”. The trash was gathered in dumps in different places at the outskirts of the city.

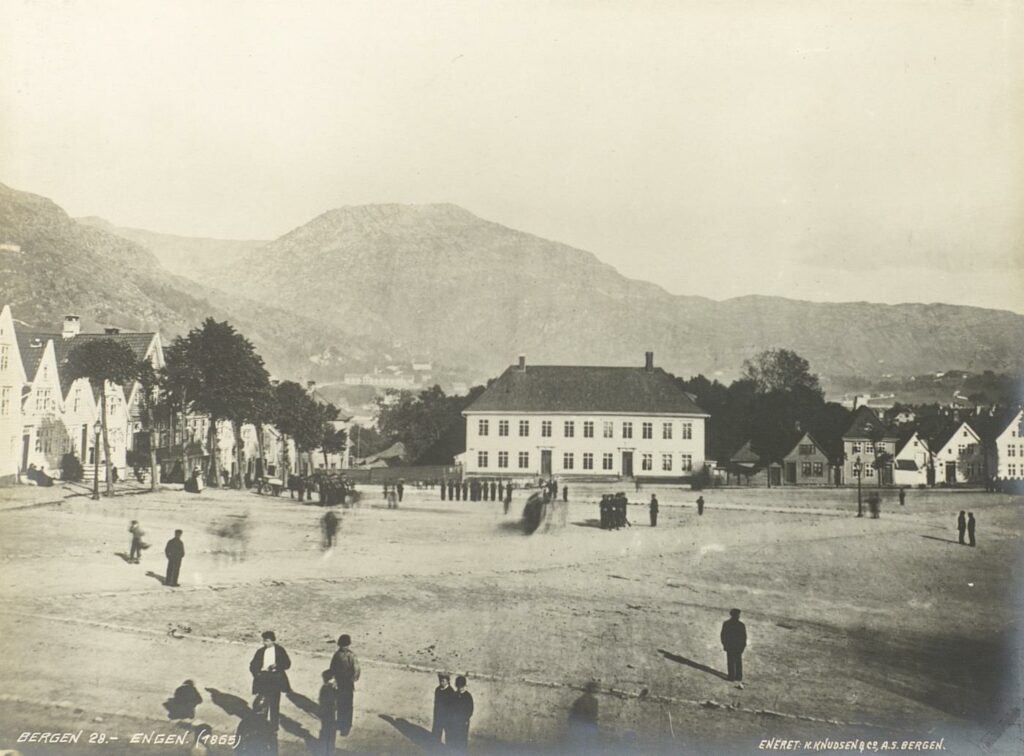

Knud Knudsen (1865) / Bergen byarkiv.

Knud Knudsen (1865) / Bergen byarkiv.When cholera came to Bergen

But a lot changed when cholera came to Bergen at the end of 1848. The deadly disease spread rapidly, first to the poorhouse Asylet where it went from room to room, then to De sjøfarendes Fattighus, and then to Tvangsarbeideranstalten, before one of the infected visited relatives at Nordnes and brought the cholera to the alleys there. In four months about 600 to 1000 infected died.

Something had to be done. A health committee and three infirmaries were established. At these hospitals cholera doctors kept disease protocols (article in Norwegian), which formed a basis for the understanding of emidemic diseases. They started to realise that the poor living conditions and sanitation amongst the poor and working class had an effect on the spread of the disease.

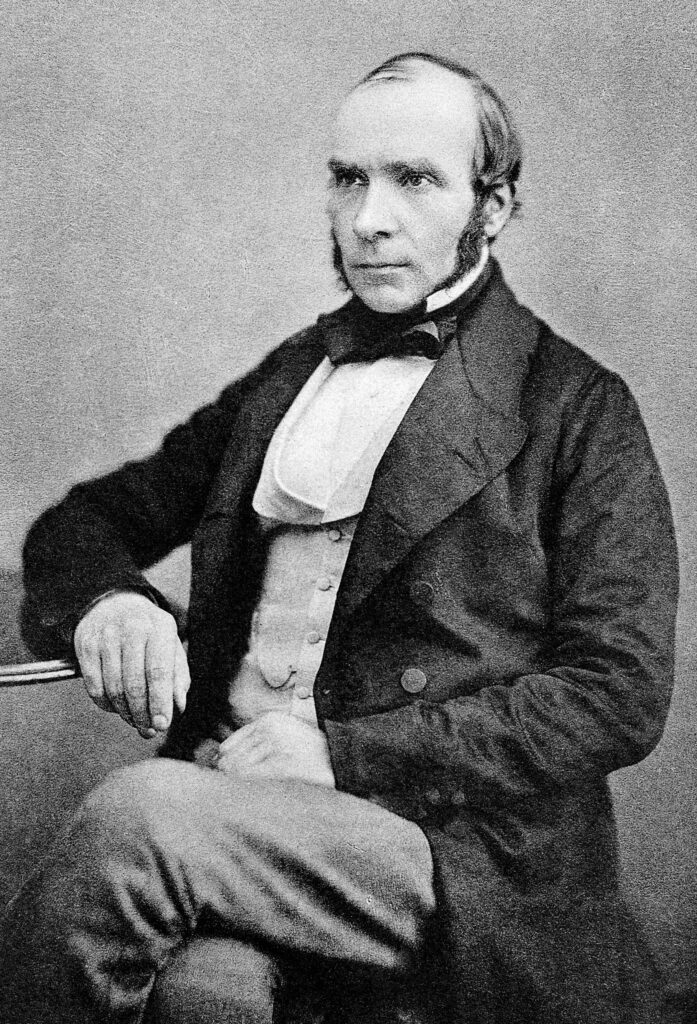

Robert Seymour / The National Library of Medicine

Robert Seymour / The National Library of MedicineThe lacking handling of waste also affected public health. In the health law of 1860 the health committee would look at what influenced the health of residents. The city got regulations concerning the cleaning of streets and courtyards.

– We were inspired by what we saw in London. We saw a connection between the spread of infection and contaminated water wells, Toralf Igesund explains. That became the basis for public daytime cleaning.

– John Snow got a saint status in the renovation industry, and that got picked up in Bergen, he says.

Ukjent / Wikipedia

Ukjent / WikipediaJohn Snow was an English physician and is today seen as one of the founders of modern epidemiology. When cholera broke out in Soho in London in 1854, the leading theory was that the infection came from “miasmas”, contaminated air. But this was incorrect, Snow though, and wrote in 1849 that the spread occurred through a public water pump.

Charles Cheffins

Charles CheffinsLocal government and water works opposed him, but he managed to document that almost all the deaths from cholera were in proximity to this well, or that the infected had drunk from it. And after Snows death Robert Koch discovered that cholera is caused by a waterborne bacteria. Snow’s work led to a drastic improvement in public health work all around the world.

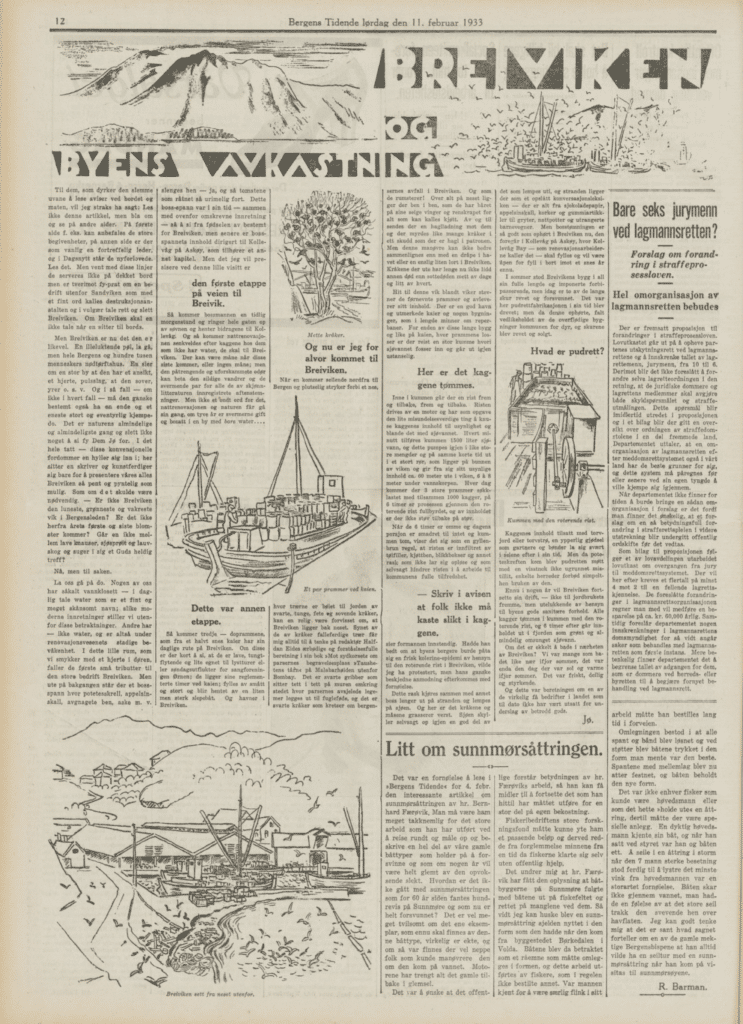

To Breivik by carriage and by boat

In 1881 Bergen renovation services were established. The private renovators were let go, and the municipality took over all renovations.

Ralph L. Wilson / Universitetsbiblioteket UIB

Ralph L. Wilson / Universitetsbiblioteket UIB– It’s been quite the development, Toralf says. In the beginning it was horse and carriage, up until the first cars were purchased.

Boats were also an important means of transportation.

6000 barrels were emptied every 14th day, and the mass was sent to a powder factory in Breiviken. There the waste from toilets was mixed in with lime and peat soil, and turned into valuable fertiliser that would be made use of in agriculture.

In 1933 a whole page in BT was dedicated to explaining about the powder factory, “Which in polite speech can be called the destruction facility and in vulgar speech simply Breiviken”. The toilets were emptied and sent there, but it was no longer “powder fabrication”. When the plant disease black scab, that attacks potatoes, came, “the powder was met with a probably not unfounded distrust.” The sale of powder ceased in 1929, but barrels were still collected from Bergen residents. That continued until 1962, before a new and effective emptying station was built which was used until 1998.

Atelier KK / Universitetsbiblioteket UIB

Atelier KK / Universitetsbiblioteket UIB“Some of us have a so-called water closet” it says in the same article, but it wasn’t “such modern facilities” that contributed to the operations in Breiviken. It was the barrels from those without running water that were sent there.

The garbage man calls the street from their sleep

The writer in Bergens Tidene describes it all so painterly:

Ukjent fotograf / Universitetsbiblioteket UIB

Ukjent fotograf / Universitetsbiblioteket UIB“Then comes the garbage man an early morning and calls the whole street from their sleep and collects the contributions to Kollevåg. And then comes the night renovator late in the evening for the barrels for those without water, those are bound for Breiviken. (…) Then comes the third – the toilet barges, which from half a dozen docks have their daily route at Breiviken. Of these are only to say, they are low, heavy flowing and poorly suited for joyrides or Sunday excursions for the singing group Ørnen; they lay their reglemented hours by the docks; are filled with big and small, and are fetched by a small but strong tug boat. And ends up in Breiviken.”

The place was a “foul smelling pit”, where black crows circled the city’s waste. Inside the basin a grate went back and forth, until everything was smashed, and after 6 hours all the contents went into the fjord. But the grate was “infiltrated with pieces of cloth, bones, tin cans and other debris that won’t be dissolved and of course prevents the grate from working to the municipality’s full satisfaction”. People shouldn’ throw these things in the barrels, the foreman said.

It wasn’t easy to sort correctly back then either.

Then what happens with the debris that ends up in the grate? “This debris is brought together with other trash further out on the beach and dumped in the sea. (…) The sea of course washes back up a good portion of what is dumped, and the beach lays there like an open lexicon – everything from chocolate wrappers, orange peels, corks and rubber articles for pans, chamber pots, and scrapped prams.”

(Article continues under the picture)

Bergens Tidende Arkiv

Bergens Tidende ArkivFrom 1929 the trash from Bergen was sent by boat to Kollevåg at Askøy, or “Kollevåg bay – as the renovation workers call it”. It was estimated that it would be open for garbage for up to a dozen years. It continued much longer, all the way up to 1975.

Bergen og Omland Friluftsråd

Bergen og Omland FriluftsrådThe trash shows up again

In 1979 work started to rehabilitate the area, and the young who visit the recreation area today can hardly imagine that this was the garbage dump of Bergens residents.

The trash is still there, and was covered in 1982, 2005, and latest in 2018, but in 2020 much of the sand was gone. In 2013 the Norwegian Environment Agency warned that Bergen municipality must investigate the situation in Kollevåg (article in Norwegian). The increase in the carcinogenic compound PCB was alarmingly high. In 2014 the municipality said that the trash had emerged in places. There were also concerns about if there were environmental toxins in the old landfill, and that this could spread.

In 2016 researchers tested the water quality, and released a hundred cod in cages by Kollevåg. After six weeks the fish showed signs of environmental distress. The liver was affected, it had poor growth, and had proved PAH-compounds in the bile. “The ocean floor in Kollevåg contains the whole spectrum of pollution sins, such as PCB, heavy metals, pesticides, and brominated flame retardants,” said professor of environmental toxicology Anders Goksøyr to BT back then.

Ukjent fotograf / Arkivet etter Bergen Renholdsverk / Bergen byarkiv

Ukjent fotograf / Arkivet etter Bergen Renholdsverk / Bergen byarkivRemediation of Slettebakken landfill

Covering is not an ultimate solution. At Slettebakken in Bergen a more thorough and lasting job has been done. The landfill that was in use 1940-1961 has been remediated and is the first landfill in Norway that is being dug up and sorted in place.

Bergen City Archive writes in the article Bossfyllingen på Slettebakksmyren (article in Norwegian) that Bergen and Årstad had to handle a steadily increasing amount of waste. In the 1930’s plans were started for a new landfill, but once the war broke out in 1940 it became hard to implement the renovation. Sea transport to Kollevåg halted. This led to Slettebakksmyren being used before draining and facilitation being completed. There was no collection for leachate, so the landfill has contaminated Tveitevannet. Today it is one of the most contaminated waters in Norway for the environmental toxin PCB.

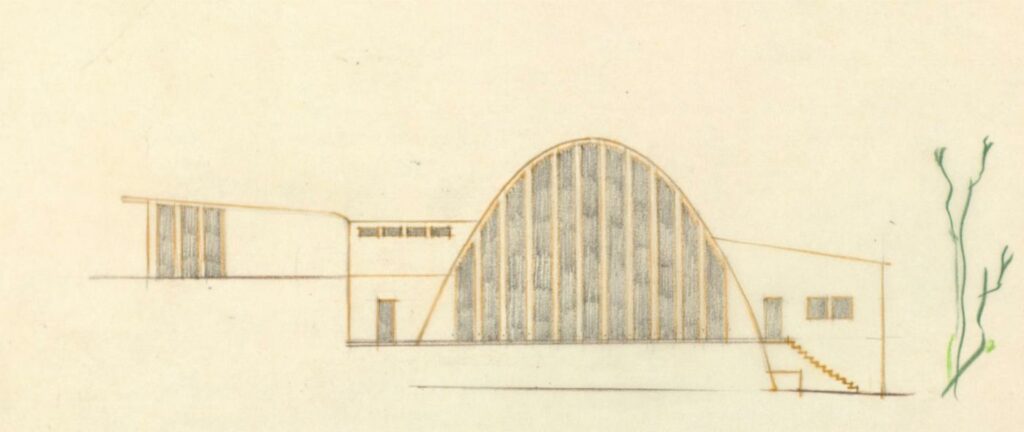

The compost facility

Garbage from Bergen also got burned in Grønneviksøren. That had been the case since 1917. But around 1930 people got tired of the smoke, the fire risk, and the increased amount of trash. A composting facility for household waste would do the trick! Because of the war Danoanlegget was not consecrated until 1960. It accepted waste from all over the municipality, but it wasn’t a success. There was little demand for compost, and the business shut down in 1979.

The garbage crisis in the 90’s

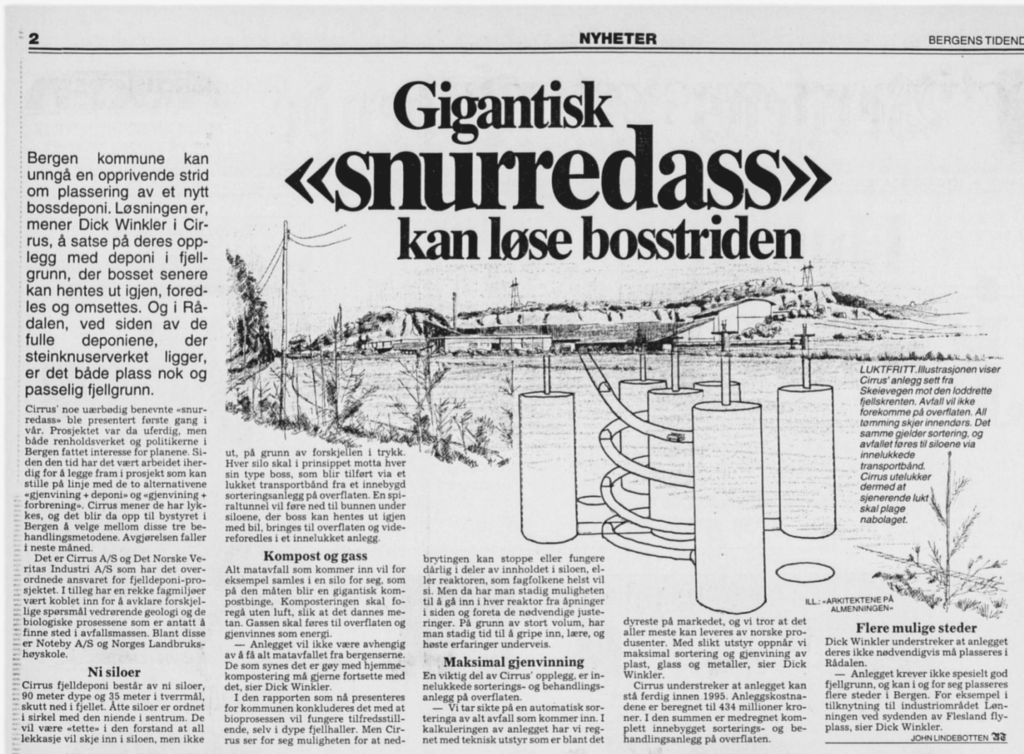

The amount of trash only went up. In fact, Bergen was headed for a garbage crisis, BT announced on the 14th of November 1992. The landfill in Rådalen would fill up, before a new solution was in place. Should we keep depositing waste? And where should the new landfill be? Or should the garbage be burned?

Not everyone was equally excited about the plans for a large incineration plant, Toralf Igesund remembers.

Kurt Oddekalv thought that we could sort ourselves out of the problem instead. But we said that we had to build an incineration plant.

Toralf Igersund, BIR

– It was a battle that took a long time. And an almost equally big case as Bybanen is today, Toralf says.

Other solutions were also proposed. Dick Winkler in Cirrus suggested a landfill in the mountain where the trash could later be brought out to be refined. Food waste could be gathered in a silo in a mountain hall.

Kurt Oddekalv was positive about this idea, because it would give the municipality a pause for thought to gather experiences with recycling waste. This was the last year he led our organisation, before he in 1993 started his own organisation: Miljøvernforbundet.

Bergens Tidende Arkiv

Bergens Tidende ArkivWe in the Norwegian Society for the Conservation of Nature (Naturvernforbundet) weren’t totally in agreement with ourselves. We can’t afford to “start up the environmental hogwash that a new large landfill or incineration plant will represent”, we wrote in BT in March 1992.

But later the same year we suggested a different solution with a smaller landfill and recycling plant in Skeisåsen/Rådalen in Bergen.

We still gave a constant no to a large incineration plant. “By starting up a recycling facility Bergen will live up to its ambition to be the country’s foremost environmental city” we stated to BT in October 1992. Waste is a resource, and therefore we wanted to invest in waste sorting. And as long as we had the option to dispose of or burn our trash, we wouldn’t be motivated to increase the recycling percentage.

It was also proposed to create a landfill in Langevatn, which we also rejected due to concern for endangered bird species.

Wanted a small incineration plant

BIR wasn’t alone in wanting an incineration plant. Terje Aasen, environmental protection manager in Bergen municipality, was also positive to this. He imagined a smaller plant that could receive 90.000 tons of waste annually, which also could function optimally with less. At the same time the municipality could still “use legal and economic means to press the degree og recycling as high as possible”. At the same time a central composting facility would be feasible.

It was also discussed if the incineration plant would be the environmentally friendly option, because incineration would drastically decrease the emission of dioxins.

The incineration plant opened in 1999, and today has the capacity to accept 200.000 tons of waste annually.

Cecilie Bannow / BIR

Cecilie Bannow / BIRIn 2022 55% of collected waste in BIR-municipalities was burned at the incineration plant in Rådalen. Thanks to the collaboration with Eviny, the heat is used in a district heating system. It’s very good that the heat isn’t wasted, but it shouldn’t be overlooked that the plant in Rådalen is the biggest single point of emissions in Bergen. 260.000 tons of CO2 is released every single year. Our consumption leads to considerable climate gas emissions.

Waste heat

When we use a machine, or any other process that consumes energy, it simultaneously produces heat. We call it “waste heat” when this byproduct isn’t utilised, but goes wasted instead. The incineration plant in Rådalen burns approximately 28 tons of garbage every hour. The heat from this process is used to evaporate water and gives electricity and heat in the district heating system. That’s enough to heat 25.000 households and electricity to almost 4000.

A solution that could counteract some emissions, is to build a carbon capturing facility connected to the incineration plant. BIR wants to start by capturing 100.000 tons CO2 annually. In the future, maybe everything can be captured. The plan is to store the carbon that is captured on the ocean floor in the Norwegian continental shelf. But this is expensive. The facility is predicted to cost 1 billion NOK.

Waiting for new EU-demands

There are also many changes happening in legislation right now.

– A lot of people are on the fence. They are waiting for new demands that are expected to come, after the EU has introduced new rules for the handling of waste and demands for how products are formed, Toralf says.

The goal of the legislative changes is to reduce the amount of waste and increase the degree of recycling. Norway follows the EU-regulations quite closely, but adapted for Norwegian legislations.

– We have high demands for waste sorting, but no one has reached the goal. Many say that we need to sort waste after collection to remove more fractions of waste. But it’s expensive. Opinions in BIR are split on whether a secondary sorting facility should be built.

– The producers should maybe also receive some responsibility, so they have to pay part of the bill. And that is also not clear yet, he says.

Stricter demands

In 2022, 26.4 per cent of all household waste that BIR received was recycled for use in other products. This is a collective percentage of the following waste types: food waste, paper and cardboard, plastic, glass and metal packaging, electric waste, scrap metal, tires with rims, park and garden waste, and plaster. Nationally 36% of household waste was reused or the materials were reused.

The first requirement for municipalities to source sort food waste, garden waste and plastic waste from households came in 2023. In the years to come this will expand to include, for the first time, demands for how much has to be recycled as materials from these categories. The first partial goal takes effect in 2025, where at least 55% of food waste must be source sorted. In 2028 plastic waste will be included in the partial goals, and 50% must be source sorted. Additionally, new demands are expected to come from the EU in the coming years that will set stricter demands for the amount of plastic required to be recycled for materials.

Demands for source sorting

Food Waste

2023: Source sorting

2025: 55 per cent

2030: 60 per cent

2035: 70 per cent

Plastic waste that can be recycled for materials

2023: Source sorting

2028: 50 per cent

2030: 60 per cent

2035: 70 per cent

Source: The Norwegian Environment Agency( Miljødirektoratet) 2023: Guidance: Sorting and recycling of waste, Waste types and demands for sorting (article in Norwegian)

Carrot rather than stick

– The day that we started with flexible fees, we also started a digital journey, Toralf says.

Those who place their bins out for collection less often, get a lower bill. People got better at sorting trash once it paid off economically.

– But it’s still not good enough. We have to test out different measures. It’ll be very demanding going forward. We believe in more carrots, not so much stick.

BIR could send people out for supervision, knocked on doors and asked how well each individual household source sorts.

– But that’s an enormous use of resources, he says.

BIR would rather follow up with a carrot. Say that, “you’re doing great!”. But that requires identifying how well each household is doing. That involves a lot of data gathering, and then we can custom tailor the follow up.

Mona Maria Løberg

Mona Maria LøbergBIR could’ve made an app, but Toralf is unsure if people would use it.

– Would they pay attention to how good they are at sorting? How many resources should we spend on this? We can’t make a system that there is extremely low interest in.

The new marking system, on the other hand, he believes has been a positive development. The marks clearly show how to recycle the product. Plastic? Residual waste? It makes it easier for the consumer to understand how to sort the product.

– I’m completely certain that it has an effect, Toralf says.

The new symbols and colours that have appeared on packaging, are being used all across the Nordic countries. The EU, too, is considering adopting the system for its member nations. Regardless, many countries will probably start using the markings.

Everything needs an address

BIR is concerned with a circular economy, and wants to contribute to making waste a resource. What does BIR mean with this term?

– We’ve thought a lot about that. We have to utilise every resource, not just recycle as materials. We’ve talked to a lot of people in the waste chain. Every material needs its own value chain. And then you need to talk to those who make the product. We need to speak and think across disciplines, more than we’ve been used to.

– We have almost no circular value chains today, Toralf points out.

Metal can easily be melted down and reshaped, but that’s not the case for all products. Many products are hard to recycle because they contain different types of materials that are hard to separate. That makes it hard to create cycles.

– Today we can have waste heat, for example, or surplus of a material. Today that is allowed, but in a circular economy this shouldn’t be permitted. Then everything needs an address, Toralf says.

– We can’t keep going like before.

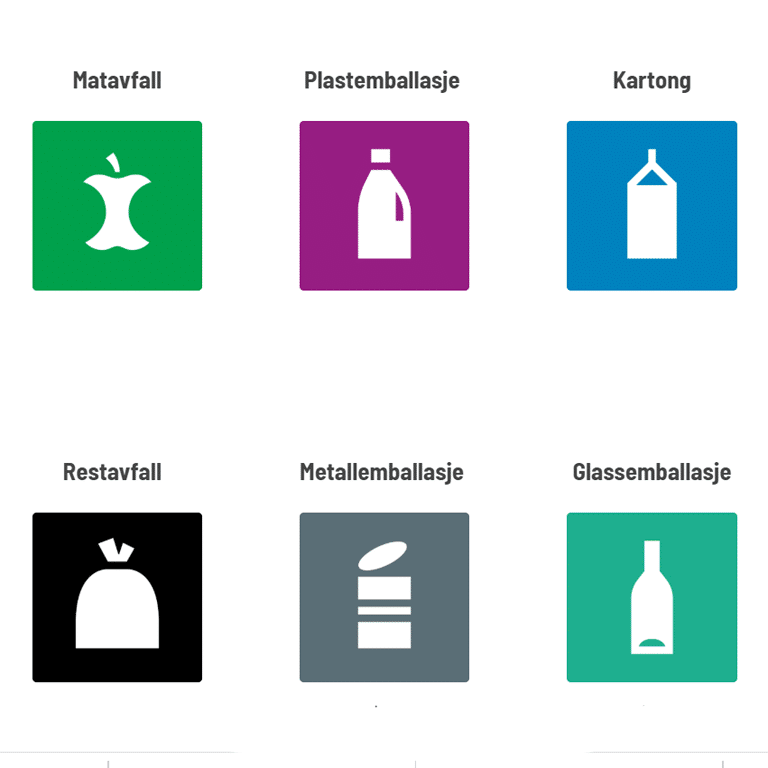

The trash in Bergen is increasing

In 2022 BIR received 376 kg of waste per resident in the region, slightly below the national average. Households have gotten better, and today we throw out about as much as in 2010.

But the bigger picture isn’t so happy. The total amount of waste has, according to SSB, increased in recent years, and that is due to higher amounts of waste from construction industries. And if we compare with 1995, the amount of waste has increased steadily.

– It’s mass production of textiles, and increased consumption, Toralf says.

– Something has to be done here, but no one wants to go back to a time with so few things.

Repair culture

Toralf continues by talking about his grandparents, who grew up in a different time with different values.

– Everything had to be maintained. There was a lot of poverty, but we fixed and took care of our clothes. We made clothes and skis ourselves. We repaired rather than buy something new.

BIR focuses on reuse during its reusing week, but BIR can’t solve the problem alone. It’s important that we talk about this, and why it is like it is.

– The problem is that it’s too expensive to repair, Toralf thinks.

– We have to work to unlearn “use and discard”. But we live in a high cost of living country, and it’s difficult to achieve. Because new things are so cheap because they are bought from low cost of living countries.

– Imagine if it could be profitable to repair! He exclaims. And the products have to be possible to repair, he points out.

Other solutions that he highlights are the option to rent things.

– Subscriptions for clothing or tools. We don’t have to own everything. Those kinds of models can also be interesting.

– The younger generations are more open to not owning a car or a cottage, but being able to access it through renting.

Talking to new industries

BIR is in contact with other renovation businesses, and they learn from each other. There is no competition between the intermunicipal companies, so they have everything to gain from sharing experiences.

There are a lot of exciting projects going on. They have started a collaboration with Invertapro, who grows insects for protein. For comparison 4-5 kg of animal feel produces 1 kg of beef, or 1.5 kg feed for 1 kg of salmon. But when producing insects there is very little waste, almost 1 kg of feed for 1 kg og insect. This also requires much less area and water.

They are also planning a biogas facility at Voss. There they can accept cow manure and food waste gathered in paper bags. From this they can produce biogas. The bioresidue is made into fertiliser, which can replace todays fertiliser products.

Toralf imagines that a lot of innovation can happen with others in the future. Who does he look up to? Germany and the Netherlands are still in the lead.

– But we have nothing to be ashamed of, he finishes.

Støttespillere i Plastjakten Hordaland 2024

News in English

Thanks to our volunteers, we have a number of articles in English.